Ask for Evidence infographic

If you’re not sure about something you’ve read or seen, follow these simple steps to #AskforEvidence? [...]

Is the study relevant?

Just because you’ve seen or been sent a reputable scientific paper, you shouldn’t assume the research actually supports the claim, even if someone has said it does. The research might well be totally irrelevant.

So first ask or check: what’s actually being tested in the study? Does it really relate to the claim?

The wider body of evidence

Even peer-reviewed research can be wrong. In fact, it often is. If a paper has been peer reviewed, you should also look out for what other scientists have to say about it, and see if you can find out whether it is part of a wider body of evidence pointing towards the same conclusions.

A single study of any kind doesn’t tell you much. And if the conclusions of a study go against the majority of research in an area, that’s a big warning sign that its conclusions may be wrong. It doesn’t necessarily mean that – but it is rare for a single piece of research to totally overturn an established body of evidence.

So always ask: how do the results fit with the wider body of evidence?

Study size

A common pitfall with studies of all kinds is that they are simply too small to make strong conclusions. Studies with a small sample size are more likely to get chance results.

There’s no magic number above which studies are big enough, but dramatic headlines are often made based on studies with only a handful of participants, and that should be taken as a red flag. If the conclusion of a small study goes against the conclusions of larger studies in the same area of research, it is likely to be wrong.

What’s the dose?

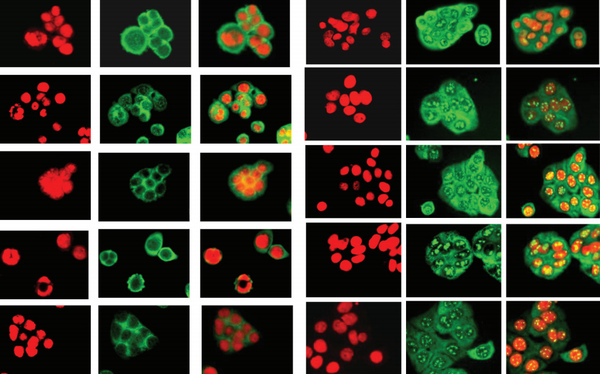

Studies in test tubes and in animals looking at the effects of a chemical can use a very high dose compared to what’s likely in the real world.

A chemical can’t simply be classified as “dangerous” or “safe”: it always depends on the amount, or dose, received. The effects of a chemical will change with different levels of exposure, so that below a certain dose it may be harmless or beneficial and at a higher dose it may be toxic. For example, a little aspirin is good for us, whereas 50 tablets could kill you.

So if a claim is being made about a ‘dangerous’ chemical based on a study, ask: what was the dose? How does that compare to likely exposure in the real world? Was the study relevant to a real-world situation?

If you’re not sure about something you’ve read or seen, follow these simple steps to #AskforEvidence? [...]

I’ve been Asking for Evidence for a couple of months now and it’s interesting how organisations respond to it. I’ve had an array of responses: Polite but dismissive….. First up [...]

Every month there are dozens of news reports about medical breakthroughs and wonder drugs. The internet is cluttered with adverts and chat-room conversations testifying to ‘amazing’ benefits. [...]

Politicians like to claim a lot of things, from how they’ve reduced unemployment to how they plan on investing in renewable energy, but how prepared are they to provide the [...]

There is a system used by scientists to decide which research results should be published in a scientific journal. This system, called peer review, subjects scientific research papers to independent [...]

If someone asks you something and you don’t know the answer, what do you do? You Google it. The internet is one the most powerful tools at our disposal, and [...]